Do you remember those teleshopping commercials where each one had the same scenario: an exhausted person for whom using some ordinary tool, such as a vacuum cleaner or mop, was equally complicated and tedious as climbing K2 in winter? Then, our telemarketer appears to help, like a knight on a white horse, and offers an ordinary mop or an ordinary vacuum cleaner as a remedy for all worries of this exhausted person. The vacuum cleaner will not only vacuum the carpet but will make you feel 10 years younger and finally you will be able to organize a big party, Jay Gatsby’s style.

Why did I evoke those 3 seconds of nostalgia? Because the Smart Notes method is something completely different than a magic mop. Taking notes this way probably will not make you younger, but it can reduce your cortisol levels if your current system of writing, remembering, storing, processing, and using the information you have learned is not very productive. Sounds good? If so, I invite you to familiarize yourself with the topic.

The conception and naming

First, let’s meet a certain gentleman. Niklas Luhmann was a German sociologist and social theorist. The world of sociology considers him one of its most outstanding representatives, mainly for creating

a theory of society (the theory of autopoietic systems). However, the fame of Niklas Luhmann also went beyond the circle of sociologists. It happened thanks to the system that allowed Luhmann to become the author of dozens of books and hundreds of scientific articles.

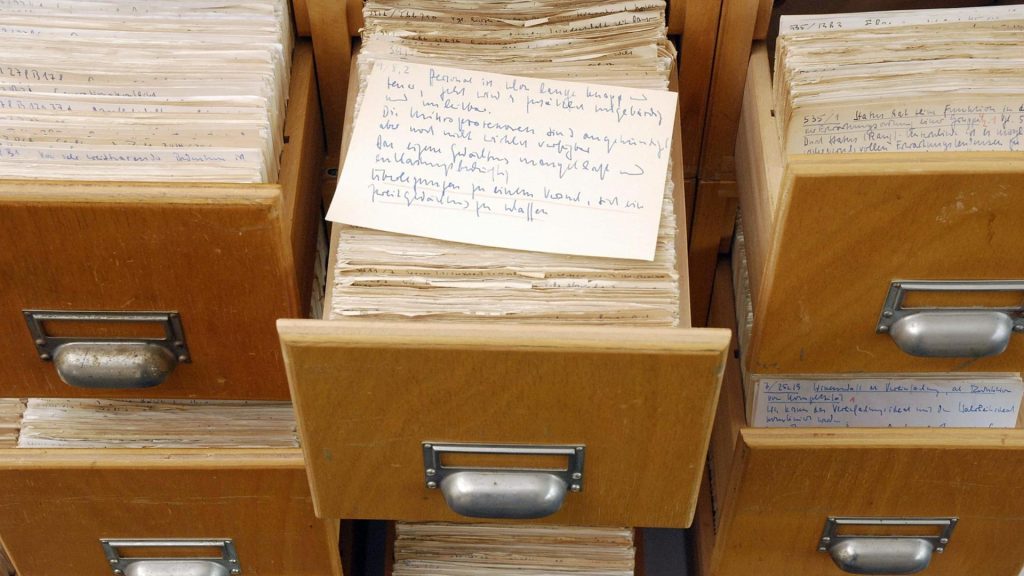

This system is Zettelkasten, also called Smart Notes. The name Zettelkasten very well describes the set of tools used by Luhmann in this method, because Zettel is German for a piece of paper and kasten is a box. The piece of paper here is an ordinary postcard-sized piece of paper and the box – well, it’s just a normal box that is big enough to hold these notes. What are these cards and boxes for? I will tell you about that in a moment.

I will also refer to the second name, Smart Notes. This name defines the idea behind this method. While the notes themselves, so far, do not have their own intelligence, the entire system allows for intelligent processing of information that reaches you. Of course, even the best system will not put knowledge into your head (for now), but if you can collect data in a way that greatly simplifies their subsequent processing and use, then why not?

What is the Zettelkasten?

We talked a little about the names of this mysterious note-taking method. But the name is not everything. So, what is this Zettelkasten, why do you need these postcards and boxes and does anyone use physical cards at all nowadays?

At the beginning, Niklas Luhmann’s professional career was related to law. After studying law, he worked in Lüneburg’s public administration. However, it was not his dream job. When off the clock, he devoted his time to reading publications related to sociology. Everything he read made him think, new conceptions sprang up in his mind. To collect all these conclusions and inspirations, he decided to take notes.

At first, he did it in the “classical” way, underlining quotes in books or summarizing some issues on a piece of paper. However, he noticed that such note-taking is inefficient and leads nowhere. Even when he organized his notes by categories or topics, something was missing. What? Connections between notes are scattered in different places. Luhmann believed that a single note was useless unless it was part of a larger puzzle.

Knowing what his needs were and what he wanted to achieve through the learning process, Luhmann found another note-taking system (he did not invent the Zettelkasten method. It was first developed in the 16th century and modified by its subsequent users and promoters). He needed it for faster and more effective exploration of issues in the fields of science that interested him.

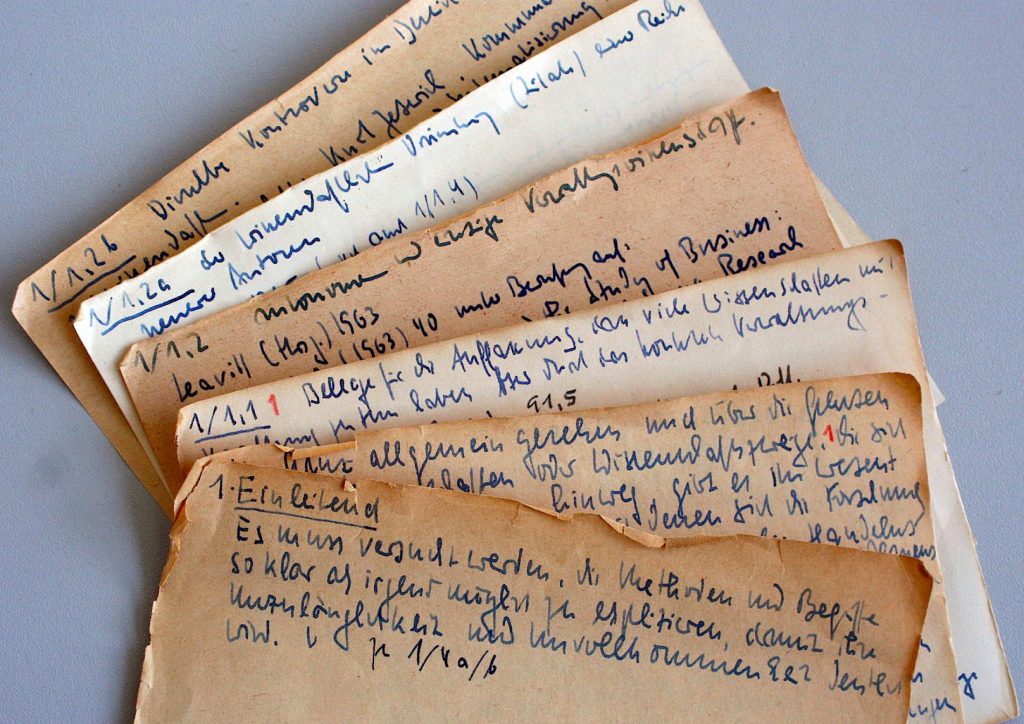

He decided to write down his thoughts and observations on pieces of paper – each thought being

a separate note cards. The notes were concise, clear, and written in full sentences. Just as if he wanted to convey a thought to another person, but without “beating around the bush”. Each note had its own ID, which made it easy to find and associate with other notes. This connection is crucial, which is why, in addition to the ID of a given note, Luhmann also added links to other related notes.

Relations

If the new note was directly related to an existing one (e.g., it was a comment on an existing note), it was given a sequential number to make the related notes as close as possible. So, for example, the first note had ID = 1, so the comment to it should have ID = 2. If number 2 is already taken, then you use, for example, ID = 1a. Thanks to this, networks of dependencies between individual ideas were created, ordering and integrating the knowledge gained in any given area.

All written cards with IDs went into the box. All in turn. With this method, you do not have to worry about the structure, categories or thematic arrangement of notes. According to Luhmann, it is important in what context you want to find a given note, not to which category it will be assigned. That is why it is enough to number the notes in a meaningful way, enabling them to be combined later.

Writing notes in your own words

In addition to relations, there is another essential thing: writing notes in your own words. Avoiding copying or rewriting entire fragments of other publications (unless you consciously decide to use

a quote) is very important, because in order to write something in your own words, you need to think about this issue for a while, so additional thoughts come to mind.

It is also proof of understanding a given problem – if you can explain something in a simple way, it means that you have mastered the material. This approach can be used when reading books. Reading comprehension, contrary to appearances, is not easy, and remembering what you have read long term – even more difficult. Probably a well-told story from a fiction book will stay in your head for longer, but when it comes to self-development or science books, it’s more difficult here. These types of books are usually full of knowledge, and if you do not have an extremely good memory, you will not remember much.

This is where the Zettelkasten comes in handy. By taking notes while reading (emphasis on the word while) you can learn and remember much more than by marking entire pages that you usually do not come back to.

There is one more benefit. It may not be useful to everyone, because not everyone writes articles or books, but it’s a nice bonus. By writing a note in full sentences and in your own words, you have a ready to go piece of text that you can use to create your own publication later on. This way, the problem of the “blank page” does not apply to you. Even when you sit down to write a new text, a large part of the work is done – all you have to do is collect your notes.

This is exactly what Niklas Luhmann did with his notes. He collected them and wrote a paper which he took to a sociology professor, who was so impressed, that he suggested a professorship to Luhmann (in my time, when I was in college, I could only get a plus for good note-taking…). At that time, Luhmann had no qualifications for the position, he did not even study sociology, but this was not an obstacle for him.

Thanks to his Zettelkasten, he was able to complete all the formal requirements in less than a year, and thus he could finally pursue a profession that suited him best. This example shows what you can aim for with small but systematic steps. The first step will be the hardest because creating notes in this system requires getting into a certain habit, but with each subsequent note written, it will get easier. Before you know it, your box will be full of ideas and insights that, combined in various ways, will show familiar issues in a completely new light.

How to start?

You already know a lot about the method itself and its advantages. You got to know the general mechanism, but how to use it in practice? Do you have to look for a shoe box and buy a bundle of note cards on which you will write down everything you can?

You can, but you don’t have to. If the prospect of a trip to the store brings a smile to your face and a sudden surge of happiness, nothing stands in the way of trying Zettelkasten in a form as close to the original as possible. If, on the other hand, you prefer to take notes digitally or simply do not want to surround yourself with boxes full of notes, there are several applications that have been created for Smart Notes. You can also use a mixed system – the method is so universal that it can be adapted to your needs.

Just remember to simply create notes whenever possible, write them in your own words, and link them together. These are the basic principles without which the method makes no sense.

Structure of notes

And what does the structure of notes created with this method look like? Sonke Ahrens, author of the book “How to take smart notes” (which is a compendium of knowledge about the Zettelkasten method), suggests dividing notes into 4 types.

Fleeting notes

These include any reminders, quick notes or seeds of ideas – generally all information that you want to keep, but you also do not have time to make a decent note of it at the moment. Let’s keep them in the place that will be your inbox. In order not to make a mess (both in the head and in the house), all notes of this type should be processed within a few days, then throw away. It is not worth keeping these notes for longer, because if after 2-3 days you do not process the recorded information, you will probably not remember what you meant then.

Literature notes

This group includes notes created during the reading process. They should be concise and written in your own words. You should avoid quotations (rewriting parts of the book on a piece of paper or simply marking them directly in the book) – unless you consciously want to use it later. Writing even a short note that paraphrases the author’s words will have a better impact on the memorization process than writing down entire pages of quotes. Such notes are best placed in your reference management system along with bibliographic details.

Permament notes

This is the result of the work you put into the processing of the first and second types of notes. There are notes written in an understandable way so that even after a few years they do not lose their substantive value. You do not throw away these notes. They should be stored in one place and should be uniform. It is important that they are written in your own words, that they represent your reasoning and are the result of your thoughts.

Project notes

It is a mix of the above types. These are notes that are created in the manner of permanent notes, but can be discarded or archived at the end of a project. They should be stored in a separate folder dedicated to a given project.

I am intentionally talking about note types here, not categories. There is no need to categorize notes. It is extra effort. Also, as I mentioned earlier, it’s better to combine notes than to categorize them. Perhaps the division into categories seems to be better in terms of organization, however, it is not about creating an archive that is visited once every 5 years. The point is to create a network modeled on neural connections that are used every day.

Creating a “neural network” from notes

What tools do you need to create such a network?

- A piece of paper and a pen (or any note-taking app on your computer or phone) – to write down everything that comes to mind and you think is worth writing down. And what is it worth saving? Everything that you will want to process later and keep permanently.

- A reference management system (e.g., Zotero) – for storing notes created, for example, while reading and for references to publications, fragments of books or articles on the basis of which you saved a given note.

- A slip-box – can be plain cardboard if you write notes by hand or an application (Obsidian or Roam Research) on your computer or phone for digital notes. All permanent notes will be stored here. And if you choose the digital version, you will be able to easily combine related notes.

- A text editor – ideally, it should be compatible with a reference management application to make everything as easy as possible.

The note-taking scheme is simple, but it takes getting used to. For example, if you read a book with the hope that you will learn a lot from it, take a piece of paper and a pen. While reading, let’s write down the most important things, maybe while reading someone else’s statement, you will come up with a solution to your own problem or you will be able to relate the author’s words to some situation from your live.

At this stage, you do not have to worry about the form – that is what you have fleeting notes for. It is important to write down the thought before it goes away and mark the source of the note. Of course, such active reading will take more time, but I suspect that reading a good book without understanding or remembering its ideas for longer is a waste of precious moments.

In the end, it is better to have one read and understood book on a given topic, from which you will have a lot of valuable notes and connections to another subject, than several, after which only annoyance remains that you have not learned anything again.

The next step will be to collect current records and create target notes based on them. Now it’s time to develop the previous ideas, compare the saved information with your own experiences, express the newly acquired knowledge in your own words and transfer it all to paper (or screen) creating a permanent note. Then you add your note to the slip-box (physical or digital) providing it with the appropriate number and/or adding to it links to existing notes with which it is associated (if you already have one).

In this way, you build your treasury of knowledge step by step. It is important to maintain regularity, to develop passing notes on an ongoing basis and, of course, to actively use the collection of permanent notes.

What to avoid?

What should we not do if we care about creating valuable notes?

Linear note-taking

Many guides talk about keeping a notebook in which you write down interesting information, ideas that come to your mind or a summary of what you learned on a given day. The very idea of keeping such a diary is good and certainly better than not taking any notes at all. However, it carries a certain danger – writing for the sake of writing.

By keeping such a diary, you fill it with lots of good ideas, but if you do not come back to them, all the great effort is wasted. Even the best system without regular inspection becomes useless. Searching for information in a notebook can be difficult unless you have a table of contents, indexes, etc. However, if someone likes this way of taking notes – it can be treated as fleeting notes. Note down in a notebook whatever comes to mind and transform it into permanent notes on an ongoing basis.

Keeping separate slip-boxes for each project

Earlier, I mentioned that one of the types of notes in the Zettelkasten method is project-specific notes. So why is having multiple “Zettelkastens” a bad idea? It is mostly about the difficulty in managing it all and the lack of connection between individual projects.

If you treat notes created from each book as a separate project, you give up the basic feature of this method – connections between information. If you treat each topic separately or categorize all the knowledge you acquire, you are not able to look at everything holistically, you do not see relationships that are not obvious at first glance, which could be captured by gathering and reviewing all your knowledge in one place.

Limiting yourself to fleeting notes only

If you note a lot and often, you accumulate a large number of materials that can significantly enrich your knowledge. However, when you are not working with these notes, you have new worries instead of new ideas. Notes multiply and it is increasingly difficult to start processing them. Therefore, simply collecting materials is not enough. Fleeting notes are essential in the learning process, but if they are not made into permanent notes, they lose their meaning.

Summary

Thank you very much for reading this article. I hope that the presented information has encouraged you to check if the Zettelkasten method is for you. If the arguments behind this method appeal to you, I encourage you to read the book “How to take smart notes” by Sonke Ahrens, which I mentioned earlier. And if you do not have time for that, I suggest to just get started – a piece of paper and a pen will suffice. And if you have questions, you can always refer to the sources or simply ask them here.

If you want to learn more about the applications that you can use to create Zettelkasten, I recommend watching the selected tutorial on the YouTube platform. There are quite a few of them, so I will give a few examples.

Obsidian:

- Morganeua: The FUN and EFFICIENT note-taking system I use in my PhD

- Morganeua: Thinking with your Zettelkasten an intro to Obsidian’s local graph view

Roam Research:

- Thomas Frank: This Note-Taking App is a Game Changer – Roam Research

Zotero:

- Steven Bradburn: How To Use Zotero (A Complete Beginner’s Guide)

Leave a comment